Dispatch from the unimaginable: what we carry after our parents are gone

Many of my friends are self-described orphans; one or both parents have already passed. Some of us grieve the abundance we were given in childhood. Some of us grieve what we needed. We are the walking wounded, without a visible cast or bandage to warn others in our path to be cautious or tender. This dispatch is for you: you who have lost the people you came from and are still aching to open the door and see them again.

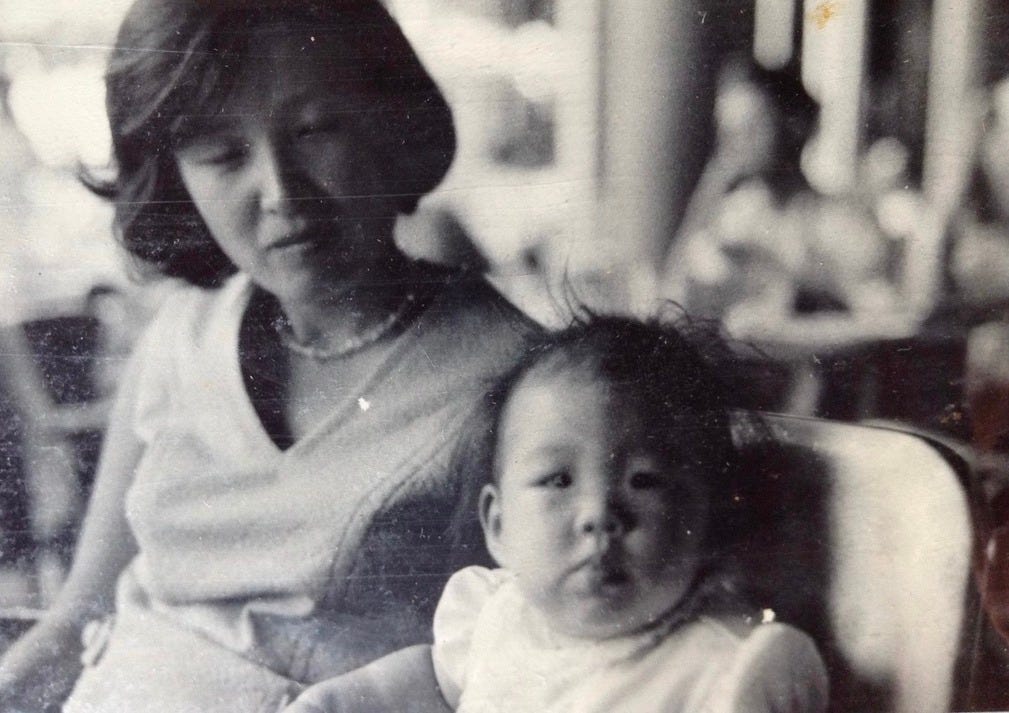

It is also a tribute to our mother Yong Jin Kim Choi.

Like so many in their generation, our parents endured unimaginable trauma they didn’t talk about. What they talked about were high expectations. They weren’t perfect but they made real sacrifices so that we had the time and freedom to explore, make mistakes and chart our own paths. What makes their choices poignant is that they didn’t make us carry the weight of their sacrifices. They didn’t burden us with guilt. My siblings and I are who we are because of the paths we chose — and because of our parents’ restraint. Looking at my mother’s life now, I see that more clearly.

To honor the fullness of her life, I’m sharing the eulogy I read at her funeral mass.

May you see some of your own beloved parent in her story. And may it remind you that they’re not gone. You might just have to slow down and listen differently.

On behalf of my sister and brother, thank you for being here to steady us with your presence, to grieve with us as so many of you have experienced this grief, and to celebrate the extraordinary life of our mother.

In July, it will have been seven years since our mother’s devastating illness. In those seven years, Hakyung has been taking incredible care of her. I think in those seven years, she and Dooho and I have been grieving. Still, we weren’t ready to let her go.

Our mother was not a prescriptive “do this do that” type of parent. She taught us by example. She showed us how to learn and explore the unknown. To be unafraid of a room full of strangers and to make friends. She showed us how to try.

But what was she teaching us by staying through so much suffering?

She stayed for us. And she stayed for you. She stayed to be present for our lives.

She saw us for what we wanted to become.

She saw her caregivers like Kumarie and Jasoda learn Korean, build a home and start RN training.

She saw in Dooho, her beloved only son, the filmmaker he worked so hard to be. And became.

What did she see in me? Well, I was not a cute baby. I was a downright ugly baby. That’s why there are no baby pictures of me in the memorial booklet. It would only prove that even hot people can have ugly babies.

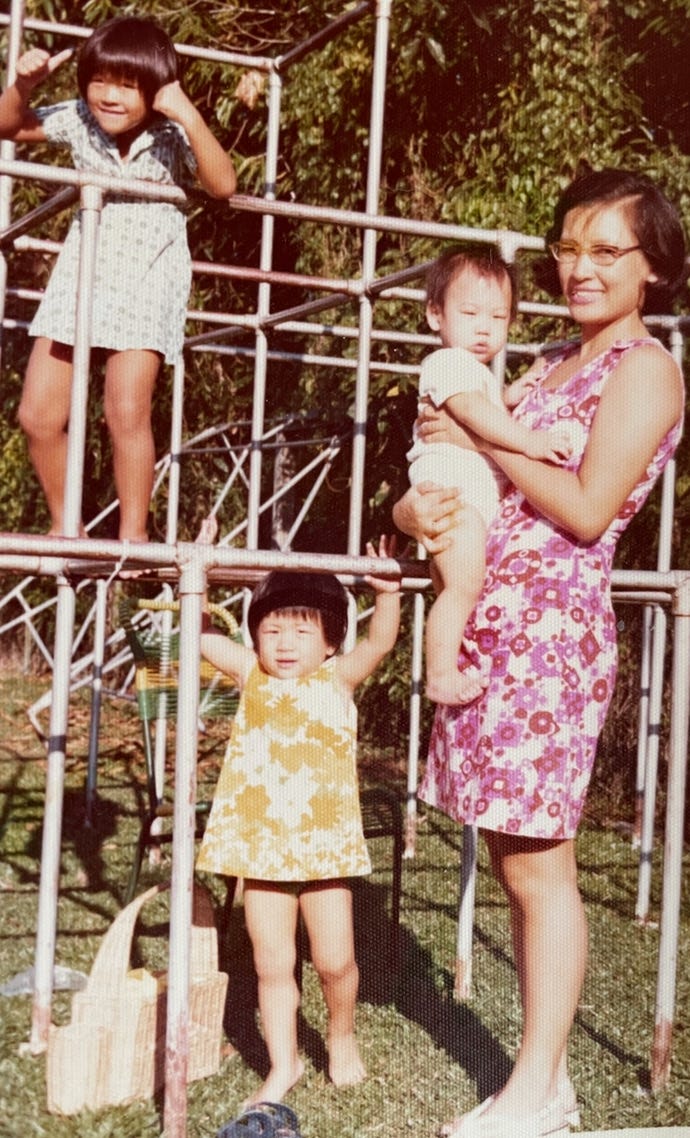

In Hakyung, she saw a sickly child she often tended to — who then blossomed into the strongest of us all.

Like so many New Yorkers, our mother looked forward to the marathon and went out into the streets of Queens and the Bronx to cheer for Hakyung, her unwavering and devoted guardian.

In kind, Hakyung saw our mother beyond her illness: for her refined taste, her love of adventure and what’s new, and her belief that she had not finished becoming.

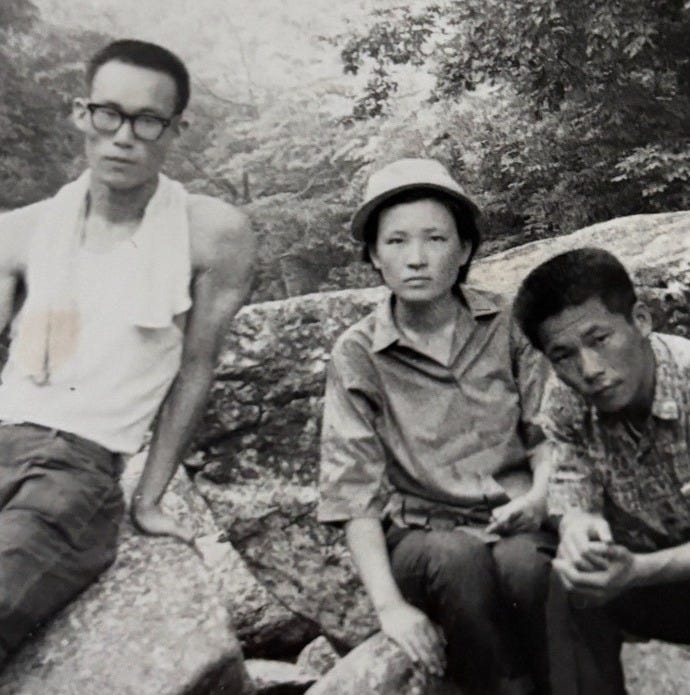

Our mother was born an Andong Kim in a country that hadn’t yet been severed by a cold war border. Her father built a transportation company back when it was like owning an airline.

But violent political changes affected the ownership of his business and fortunes. And violent political changes in modern Korea affected the destiny of his youngest daughter — our mother — and her family.

She attended the prestigious Kyunggi High School, considered Korea’s first modern high school. Some of her classmates are with us today: 감사합니다. And after graduating magna cum laude at Sogang University — 감사합니다 to her classmates here with us — she crossed an ocean to America on PanAm back when it felt as impossible as going to the moon.

She settled on unfamiliar soil for a scholarship to earn her Master’s in Anthropology at the University of Hawaii’s East West Center. She married our father, a journalist who became a diplomat.

They led what looked like an exciting life on the outside and a more conflicted one within. After all, she had great academic promise and her and her family’s outsized accomplishments and ambition. But she had to raise three children in foreign countries.

In that bargain, she discovered a problem that would pique her academic and entrepreneurial instincts and send her on another journey.

My suburban NY social studies textbooks barely mentioned Asia. And completely erased Korea.

She was fuming. And she did something about it. She built a bridge, from scratch.

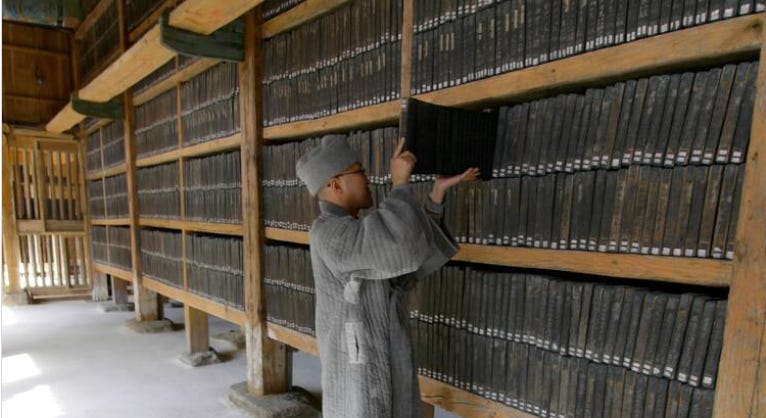

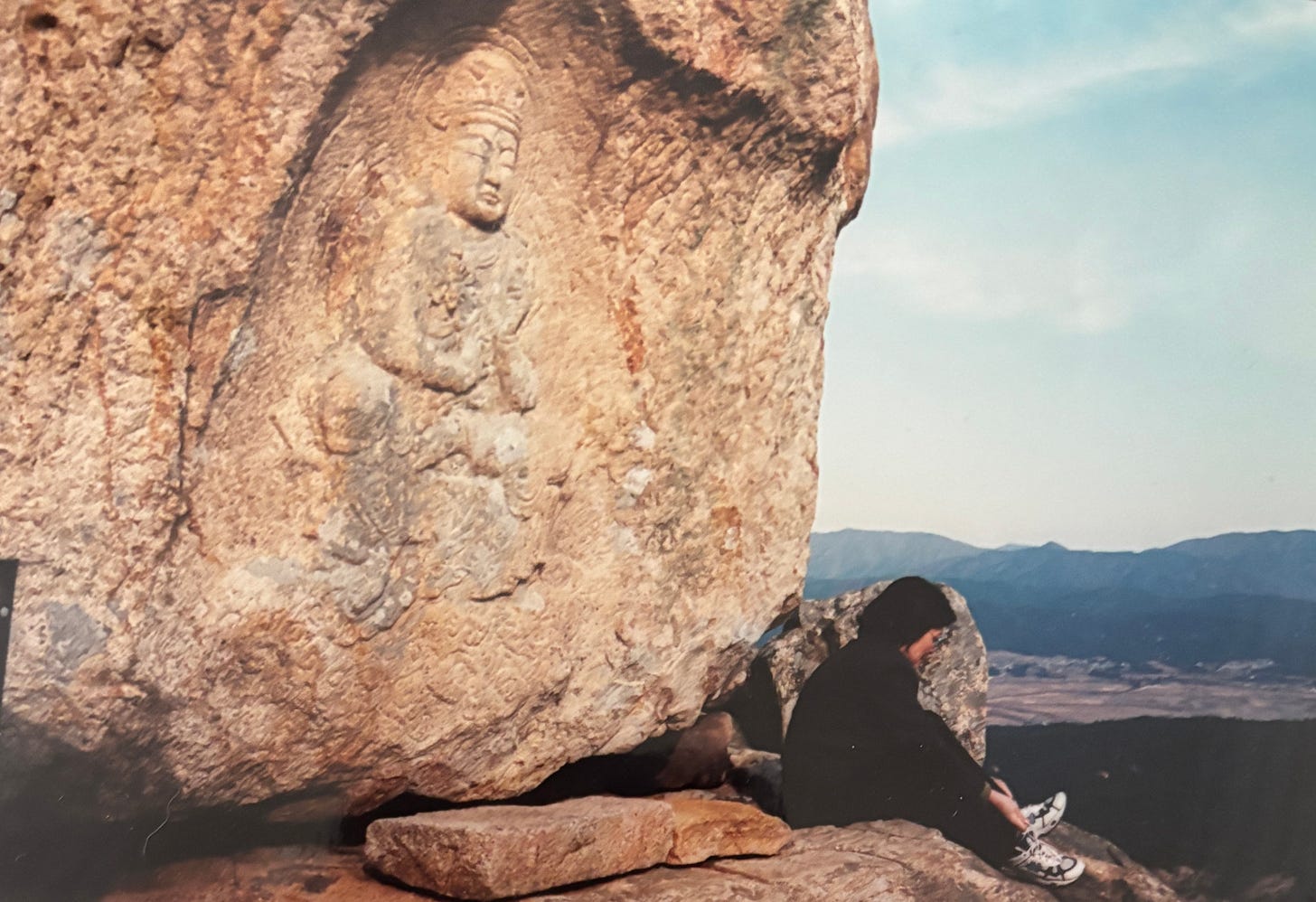

She started and operated a prestigious fellowship that brought US teachers to Korea. What they knew of Korea was the Korean War and the DMZ. Many social studies teachers had never traveled internationally nor stepped inside a Korean home. Some had trouble climbing 108 steps to reach Haein-sa temple.

Our mother was their sophisticated and scholarly guide, giving them the most insider access imaginable to Korea. She partnered with scholars, historic monuments, monks and The Korea Society. She published award-winning curricula. She made Korea visible.

Through her Korean Studies Fellowship, educators, textbook writers, museum curators saw the Korea she saw. She won the Association for Asian Studies’ Franklin R. Buchanan Prize for outstanding curricular material. In 2002, she received a presidential citation from South Korean President Kim Dae Jung for her contributions to the country.

.In retirement, she kept learning. Tended to her garden, taught herself to play guitar, learned to sing. Studied calligraphy with Choi Il Dan 선배님.

She was that person in your friend group who made everything happen. “Wouldn’t it be great if we went to Xinjiang or Sri Lanka or Kilimanjaro?” turned into organized journeys. She made it happen. Walking in pilgrimage through the Camino de Santiago Spanish coast. And yes, she climbed Kilimanjaro after retirement.

Once, my siblings and I were alarmed to read about a coup in Turkey. We didn’t hear from her for days and when we did, it was: “What? I’m busy. In Cappadocia.”

Of course. As a child, she knew to stay quiet on top of a train while escaping North Korea. She had lived through life-changing presidential assassinations and a military coup in the 1980s.

She came from a generation that weathered seismic shifts: societal, political, technological, emotional. We have language for what they endured: generational trauma. They simply lived it.

“You need us to say ‘I love you?’”

She said that love to us by staying.

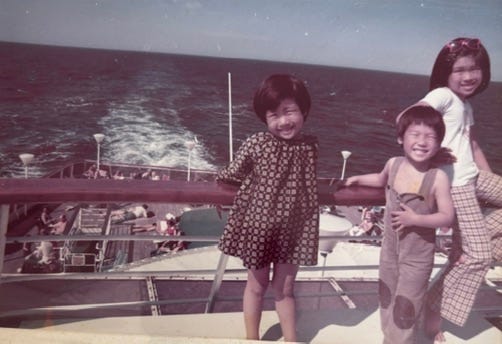

But she wasn’t inflexible. She was learned and sophisticated, modern and playful. In the 1970s when we were living in Sweden, I was almost kidnapped by North Koreans. Soon after, it was decided that we’d leave the country. But before we did, one of our parents (most likely our dad!) said: let’s end our stay with an educational cruise through the Baltics.

What else could go wrong… and when would we have another chance?

Well, the ship had North Korean passengers.

Our nervous parents begged us to stay quiet. Don’t. Speak. Korean.

But of course, we children could not be contained. We busted out of our cabin and ran up to the deck. We drank in the ocean air and sang songs loudly. In Korean.

I get what she must have been going through: after all, one of her children had almost been kidnapped.

We were in big trouble but I also caught her beautiful face, laughing. She was delighted by our defiance.

She knew how it felt to go your own way.

“There are better things ahead than any we leave behind.”

C.S. Lewis

She hasn’t gone. She has gone ahead, as she did all her life, toward the unknown.

So what do we do now?

We live in the direction she pointed. We do all the things. We climb the mountains. We march for women’s rights – again. We vote our values.

We stay with the ones who suffer.

We tell people how much they mean to us.

We show up for the people we love.

Hakyung said our mother was the love of her life. Love like that doesn’t leave us. They become part of the air we breathe.

And when we climb, or sing, or fight injustice, or dare to go somewhere we’ve never been, she will be there. She has already gone ahead.

She sees us for what we want to become.

And she is in what happens next.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made in memory of Yong Jin Choi to Parkinson’s Foundation or the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

This is an incredible tribute! I am a benefactor of your mom’s gracious and focused intention to create more accurate and robust content in American classrooms that represents the beauty of Korean history and culture. I will never forget my time with the her and the opportunity to be a part of the Korean Society. This gifts of opportunity and knowledge that your mom bestowed upon me I has continued to uplift me in my life and in my work. May you and your family continue to be blessed as I was by your mom and the Korean Society.

Wow, Christine. Your mother sounds like an incredible human that truly made a mark on this crazy world we live in. Thank you for sharing this beautiful tribute.